The Reformers didn’t just protest; they sang. The Protestant Reformation, which began in earnest 500 years ago this week, didn’t just give birth to preaching and writing, but it inspired music and unleashed song.

That God declares us rebels fully righteous on the sole basis of his Son, through faith alone — such news is too good not to sing. And that our Creator and Redeemer himself has spoken into our world, and preserved his speech for us in a Book, to be illumined by his own Spirit — such news is too good not to craft into verse. Perhaps the greatest evidence that the Reformation released real joy in freeing captives from the bondage of man-made religion is that its theology made for such a good marriage with music. The Reformation sang.

Battle Hymn of the Reformation

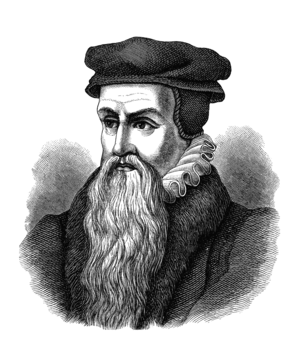

Leading the way not just in word, but in song, was Martin Luther. He wrote nearly forty hymns, many of which he composed not only the words but even the music. His most famous, of course, “A Mighty Fortress,” often is called “The Battle Hymn of the Reformation.” The song embodies with strength and gusto the very spirit of the Reformation, breaking free from the flaccidity and poverty of medieval theology with rich God-confidence.

The hymn takes its inspiration mainly from the first two verses of Psalm 46, along with the refrain of verses 7 and 11.

God is our refuge and strength,

a very present help in trouble.

Therefore we will not fear . . . (Psalm 46:1–2)

The Lord of hosts is with us;

the God of Jacob is our fortress. (Psalm 46:7, 11)

Psalm 46 opens with God as “refuge and strength,” and the battle hymn opens with God as “mighty fortress” — literally, a strong or unshakable castle. Line three is “help in trouble”; stanza three is “we will not fear.”

But that’s where the parallels end. Rather than a mere hymnodic expression of the psalm, we do better to call it a Christian hymn inspired by it. What’s generic in Psalm 46, Luther makes specific, and Christian. He names the personal agent behind the trouble: “our ancient foe,” the devil. He puts a human face and person to the rescue: “Christ Jesus it is he.” And the hymn apexes with the glorious Himalayan peaks of Romans 8.

How Did We Get the English?

Perhaps at this point, or sometime in the past, you’ve wondered about the English version we sing today, Hey, didn’t Luther speak German? Who brought this powerful hymn into English, and how faithful is it to Luther’s original?

“The Reformers didn’t just preach and write. They made music and unleashed song.”

The hymn came into English as early as ten years after Luther composed it, but the version most of us sing today was translated by Frederick Hedge more than 300 years later, in 1853. It is by no means a literal translation of the original, understandably taking certain licenses for the sake of meter and rhyme. Add to that the fact that Hedge was a Unitarian minister — meaning he believed in God’s oneness but not threeness. In other words, he was no Trinitarian. He believed Jesus was fully human but not God, inspired by God but not his eternal divine Son.

To give Hedge his due, his English version well embodies the mood and major themes of Luther’s original. “Mighty fortress,” admittedly less familiar imagery for us, captures Psalm 46 better than what comes to our minds today when we think of a “castle.” What’s in view in the psalm is first strength, not beauty. Think Helm’s Deep, not Disneyland. And we can thank Hedge for his powerful quatrain, alluding with Luther to Luke 21:16–18, at the finale:

Let goods and kindred go

This mortal life also

The body they may kill

God’s truth abideth still

What the Unitarian Lost

However, we shouldn’t be too surprised that a Unitarian translator might miss some things, both small and large — some intentionally and others unavoidably, given the nature of translating lyrics as opposed to prose. To help you better enjoy the power of Luther’s original, let’s note seven variants, thanks to a “woodenly literal” translation by John Piper, reviewed by German pastor Matthias Lohmann. (The full translation is posted below.)

1. Offense, Not Just Defense

Hedge’s second line says God is “a bulwark never failing.” What we miss from the original is that God, our Mighty Fortress, is not only defensive but also offensive — literally, “a good defense and weapon.” He not only protects but leads us forward into victory.

2. Help from Every Misery

In crafting his poetic lines, Hedge says God is our helper “amid the flood of mortal ills.” Luther’s original is more sweeping: “he helps us get free from every misery.” This is the major theme we see emerge: Luther’s is stronger.

3. Luther’s Wonderful Extreme Statements

“As strong as ‘A Mighty Fortress’ is in our English, it is even stronger in its undiluted, original form.”

Speaking of every, Hedge’s translation consistently softens Luther’s extreme statements. Which means that as strong as “A Mighty Fortress” is in our English, it is even stronger in its original form. Not only does our God, our Mighty Fortress, free us from “every misery,” but “With our power nothing is accomplished / We are very soon lost” (compare with “Did we in our own strength confide / Our striving would be losing”). So also, Satan “does not do anything to us” is a more forceful claim than simply “his rage we can endure.” And related to our “goods and kindred” (literally, “goods, honor, child, and wife”), Luther asserts, “They will have no profit,” which Hedge leaves out altogether and fills the gap with “God’s truth abideth still.”

What’s lost in Hedge softening Luther’s edges? Luther’s extremes better capture not only God’s extreme fullness and power, but also our extreme emptiness and powerlessness.

4. God Works All According to Plan

We said above that the hymn culminates with Romans 8. Not only is Satan utterly unsuccessful in his efforts against us (Romans 8:31), but in the final stanza, Luther alludes to Romans 8:28, with Ephesians 1:11: “[Christ] is with us according to plan.” Hedge again says less (“Through him who with us sideth”), opting just to capture “with us” but not the divine sovereignty of “according to plan.”

5. The World Could Be Much Worse

Hedge’s “though” at the outset stanza three introduces a subtle difference worth noting. “Though this world with devils filled” concedes a magnitude to the evil presently at work in our world that Luther did not. He did not think the world was full of devils. Devils enough, for sure, but not a world full of them. Luther says “even if.” He raises a hypothetical to make a case for God-confident faith now. “Even if the world were full of devils” — and it is not full of devils, but just one — but even if this were the case, “We would not thus fear so very much / We will nevertheless succeed.”

Luther aims to conquer fear, and feed faith, in the present by asserting that even if our plight was much worse, we would still be utterly secure in Christ. How much more should we now rest secure in his unshakable sovereignty!

6. No Other God Than Jesus

Most significantly, the Unitarian drops Luther’s reference to Jesus as God. Hedge inserts “from age to age the same” in place of “there is no other God.” This is the greatest of Luther’s extreme statements that doesn’t make Hedge’s cut, and this is the single biggest oversight or alteration. Might it not be fair to assume alteration since Hedge was Unitarian?

It is gloriously true that Jesus is the same yesterday, today, and forever (Hebrews 13:8), but that’s not what Luther had in his original. Rather, it seems to have made the Unitarian squirm, and he sought to rescue this otherwise strong hymn from what he thought was Trinitarian error.

7. His Kingdom Is for Us

Finally, Hedge’s last line (“His kingdom is forever”) loses Luther’s “for us” (literally, “The kingdom must remain for us”). It’s a small loss, yes, but sweet and important. This is the great for-us-ness which the Reformation so wonderfully recaptured. In Christ, we not only catch a glimpse of God’s spectacular kingdom, but we’re invited in. We become part of the reign from the inside (even, in some real way, reigning with him, 2 Timothy 2:12; Revelation 20:6) — in a kingdom that not only remains forever but is for us, for our eternal good and everlasting joy.

So, this weekend, and into the future, as we enjoy Hedge’s admirable translation — for which we should be thankful — we can rest assured that Luther’s original is even stronger, and even better. And Psalm 46 and Romans 8 are even better, and even stronger, than what Luther could capture in verse. The God we sing about will always be stronger, and better, than even our best songs can say.

A Mighty Fortress Is Our God

A “Woodenly Literal” Translation

by John Piper, with Matthias Lohmann

A strong castle is our God,

A good defense and weapon.

He helps us become free from every misery

That has now affected us.

The old evil enemy

Is now in earnestness with his intents.

Great Power and much deception

Is his cruel armor.

On earth is not its likeness.

With our power nothing is accomplished.

We are very soon lost.

The right man fights for us

Whom God himself has chosen.

Do you ask who that is?

His name is Jesus Christ,

The Lord of hosts,

And there is no other God.

The battlefield he must hold.

Even if the world were full of Devils

And would want to swallow us up,

We would not thus fear so very much.

We will nevertheless succeed.

The prince of this world,

How bitterly he might pretend to be,

Nevertheless will not do anything to us

Because he is judged.

A little word can fell him.

That word they shall let stand

And will have no thanks for it.

He is with us according to plan

With his Spirit and gifts.

If they take the body,

Goods, honor, child, and wife,

Let them go away.

They will have no profit.

The kingdom must remain for us.

Over a hundred years ago, the great Dutch theologian Hermann Bavinck predicted that the 20th century would “witness a gigantic conflict of spirits.” His prediction turned out to be an understatement, and this great conflict continues into the 21st century.

Over a hundred years ago, the great Dutch theologian Hermann Bavinck predicted that the 20th century would “witness a gigantic conflict of spirits.” His prediction turned out to be an understatement, and this great conflict continues into the 21st century.

Recent Comments