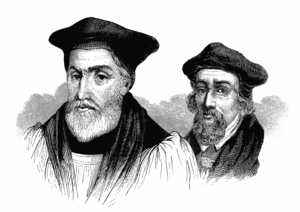

Hans Gooseflesh

c. 1400–1468

The Accidental Reformer

By Rick Segal

Hans Gooseflesh came of age at the turn of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries when the prevailing spirit of the age was “God must be angry.” His parents and grandparents were the generation that watched the Black Death eliminate a third of the continent’s population. In some European villages as many as sixty percent of the people perished.

He was born into an upper-class family. Dad was a goldsmith — “Companion of the Mint” they called him — a maker of coins and medallions. As he roamed around his father’s shop as a boy, he no doubt marveled at and probably even assisted in the process of striking coins. Molten metal was poured into molds (imagine tiny cake pans with scripts and images already debossed in the pans). The mold was made from a die strong enough to punch a clean impression of the coin onto it. The die itself was meticulously engraved by hand into tempered steel by craftsmen using sharp jeweler-like tools capable of removing steel from steel as easily as shaving a butter pat from the stick.

Failed Start-Up

Alas, Hans was not to inherit the family business. An uprising of guildsmen against the employers, which included Hans’s father, caused the family to relocate to Eltville. So, Hans needed to seek other job opportunities.

In the wake of the plague’s devastation, Roman Catholicism fostered an extraordinary consumer market in religious goods and services. Beyond the peddling of everyday rosaries, tokens, icons, and crucifixes to supply the faithful and penitent, a booming tourist industry emerged attracting hundreds of thousands of Catholic pilgrims eager to see relics recovered from the Holy Land.

An Ox Eye was a badge with a mirror on it that you could wear when visiting displayed relics. The idea was if the mirror on the badge caught the reflection of a relic, well, how couldn’t you be blessed? The Cathedral of Aachen housed four so-called Great Relics then, and still does: Mary’s cloak, Christ’s swaddling clothes, St. John’s beheading cloth, and Christ’s loincloth.

Hans Gooseflesh formed a start-up aimed at cornering the market for Ox Eyes at the 1439 Aachen pilgrimage, projected to draw more than 100,000 pilgrims. Leveraging his expertise in coin-making, he planned to mass produce 32,000 Ox Eyes and make a 2,500-percent profit on the venture. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a bad attendance year. The venture failed. Hans and his investors lost their shirts. But in the process of engineering Ox Eye production they created some significant intellectual property.

Lemons into Books

Knowledge transfer was shifting from oral transmission to inscribed manuals, directories, stories, and histories. People wanted books. Most of the demand was supplied by copyists and scribes who, when working earnestly, might be able to knock out a single — and we do mean single — volume of a Bible commentary once every five years. The innovation of woodblock printing helped the uptake of book supply, but woodblocks were unforgiving to error, easily breakable, and limited to a single use.

Hans Gooseflesh made lemonade from the lemon of his failed Ox Eye start-up. In the process of figuring out how to make souvenirs for the Aachen pilgrims, he conceived of a method of building forms into which a collection of metal characters could be racked to create, if you will, a “metalblock” rather than a woodblock that could be used to print sharp, readable words on a page, and then be un-racked, re-ordered, and reused to create new forms for entirely different projects. It was a variation of the die, mold, and punch-making of his childhood performed in miniature to muster legions of metal mercenaries perpetually ready for redeployment.

History Reset

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (anglicized here as “Hans Gooseflesh”) was dead fifty years before Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the door. He never preached a sermon. Never authored a theological treatise. Indeed, Hans Gooseflesh, apart from his eponymous Gutenberg Bible, did a banner business in printing papal indulgences. He was a Reformer only by accident — or, better, by common grace. But the printing industry’s quick standardization to Gutenberg’s system of movable type created a production and distribution capability that enabled Luther’s titles to occupy thirty percent of an unheard of seven million–book market in Germany between 1518 and 1525.

The Chinese had invented moveable type seven centuries before, but their writing system was too complex to make use of it. The Muslim world resisted the use of printing for four hundred years after the invention of moveable type. So, in one unique window of human history, God raised up a ne’er-do-well tchotchke-maker to pave the way for a spiritually tortured monk, and his successors, to reclaim the word of God and reset the history of redemption.

Recent Comments