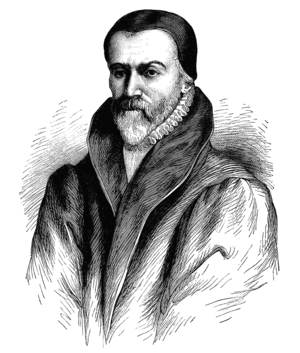

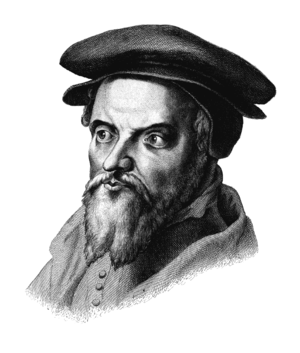

Thomas Cranmer

1489–1556

The Gospel Lobbyist

By Matthew Westerholm

As King Henry VIII lay dying in his bed, he wanted one man to come and hold his hand. Amazingly, that man was a major proponent of the Protestant Reformation.

Thomas Cranmer helped lead the English Reformation, but he is an unlikely hero alongside Luther, Calvin, and the other Reformers. He did not write any major theological books or pastor any important churches. Indeed, Cranmer did not adopt the central truths of the Reformation until relatively late in his life. But during the years of the Protestant Reformation, he shaped English theology perhaps more than any other person who has ever lived.

The Seed of Separation

Born in 1489, in the small village of Aslockton, Thomas Cranmer grew up near the same Sherwood Forrest where Robin Hood hid out three centuries earlier. He was a slow reader, taking eight years to finish Cambridge’s four-year undergraduate degree. He persevered in his studies, completed a masters degree, was ordained into ministry, and was elected by Cambridge to teach. He built a reputation for pushing his students to study the Bible for themselves.

While Cranmer spent his days peacefully serving on academic committees, England was in turmoil. King Henry VIII wanted to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Through a strange set of circumstances, Cranmer suggested to some of Henry’s advisors that the King of England was not ultimately subject to the pope’s rule (much to the king’s delight). Cranmer’s advice, then, inadvertently planted a seed that separated the English church from Roman Catholicism.

The Reformed Politician

Cranmer traded away Roman Catholicism for Reformed doctrine by the end of his life, a transformation that mirrored the turmoil and split of the English Reformation. While a student at Cambridge, he had read Martin Luther skeptically, but he warmed to Reformed thought after befriending Simon Grynaeus and Andreas Osiander. He eventually rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation after conversations with his friend Nicholas Ridley. Cranmer then clarified his liturgical reforms through conversations with the Italian Reformer Peter Martyr and the German Reformer Martin Bucer.

Cranmer’s theology changed too dramatically for English Roman Catholics and too slowly for Reform-minded evangelicals. To some (even today), Cranmer’s reforms seemed too personally and politically motivated. But he did not have the luxury of working out abstract beliefs among a company of disinterested academia. His theology was formed in a volatile pastoral and political cauldron of crises.

Father of the Anglican Church

Cranmer’s greatest ministry accomplishments came during the rule of Edward VI, when he rewrote the public liturgies, pastoral sermons (or homilies), private prayers, and articles of faith. These writings defined the doctrinal framework and personal piety which later developed into the Anglican Church, for which he is most remembered.

Cranmer wanted everyone in English churches to embrace justification by faith alone. He wrote,

This proposition — that we be justified by faith only, freely, and without works — is spoken in order to take away clearly all merit of our works, as being insufficient to deserve our justification at God’s hands; and thereby most plainly to express the weakness of man and the goodness of God, the imperfectness of our own works and the most abundant grace of our Savior Christ; and thereby wholly to ascribe the merit and deserving of our justification unto Christ only and his most precious blood-shedding. (The Works of Thomas Cranmer, 131)

Double Recantation

When the Roman Catholic Queen Mary I took power, Cranmer’s Reformed convictions cost him his life. During an agonizing three-year period, he was imprisoned, isolated, humiliated, interrogated, and tortured. He was forced to watch his friends, Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer, burned alive.

Later, at his own execution, Cranmer nearly succumbed and recanted his beliefs, but this usually hesitant and quiet statesman powerfully demonstrated his faith in Christ while being burned at the stake.

The Thief on the Throne

But the moment that best illustrates Cranmer’s enduring legacy was not the day of his own death, but a day nine years earlier, as he stood at the deathbed of King Henry VIII. On January 27, 1547, King Henry was dying. An attendant asked him whom he wished to have at his bedside. The king asked for Thomas.

By the time Cranmer arrived, King Henry was unable to speak. Foxe tells the story.

Then the archbishop, exhorting him to put his trust in Christ, and to call upon his mercy, desired him though he could not speak, yet to give some token with his eyes or with his hand, that he trusted in the Lord. Then the king, holding him with his hand, did wring his hand in his as hard as he could. (Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, 748)

The scene sweetly punctuates the most important friendship in the English Reformation. Whatever King Henry believed when he squeezed Cranmer’s hand that day, God used the bond between them to break England free from Roman Catholicism and to recover the one true gospel.

Recent Comments