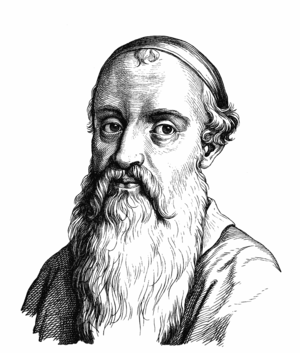

Menno Simons

1496–1561

The Fearless Pacifist

By Ryan Griffith

If you are familiar with the contemporary Mennonites, you may be surprised to learn that the group’s founder started as a Catholic priest who had never read the Bible.

A Priest Without the Bible

In 1524, at the age of 28, Menno Simons was ordained a priest of the Catholic Church in Utrecht, Germany. Although familiar with Greek and Latin and studied in Catholic doctrine, Simons had never read the Scriptures themselves. “I had not touched them during my life,” he later wrote, “for I feared if I should read them they would mislead me.”

In 1526, he began to question the truthfulness of the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation (the idea that the bread and wine transform into the actual flesh and blood of Jesus in the Eucharist). Simons thought this doubt might be the devil deluding him, so he reluctantly began to study the Bible. While he could nowhere find the doctrine of transubstantiation, he discovered the gospel of salvation by grace through faith in Christ! He began sharing his discoveries with others from the pulpit, propelling him to a place of regional prominence as an evangelical preacher.

Smoke but No Flame

Simons’s study convinced him of the Bible’s unrivaled authority, leading him to examine Catholic doctrine in Scripture’s light. He also rejected the practice of infant baptism as unbiblical and began to encourage congregants to be baptized in accordance with their confession of faith in Christ. Despite his embrace of evangelical doctrine, he remained a priest in the Catholic Church and worked for its reform. All the while, however, his fascination with biblical teaching was merely intellectual. He relished the sweet smell of his newfound fame but lacked the pure flame of true affection for Christ.

The execution of three hundred Anabaptists at Old Cloister near Bolsward in April 1535 brought him to the point of crisis:

I reflected upon my unclean, carnal life, also the hypocritical doctrine and idolatry which I still practiced daily in appearance of godliness, but without relish. My heart trembled within me. I prayed to God with sighs and tears that he would give to me, a sorrowing sinner, the gift of his grace, create within me a clean heart, and graciously through the merits of the crimson blood of Christ, forgive my unclean walk and frivolous easy life.

Overcome by his sins of pride, timidity, and love of comfort, Simons decisively renounced his “worldly reputation, name and fame.” “In my weakness,” he wrote, “I feared God; I sought out the pious and though they were few in number, I found some who were zealous and maintained the truth.”

Enemy of the State — and the Devil

After being baptized, Simons immediately threw himself into preaching the gospel, explaining the Scriptures, and traveling extensively. Simons discovered that the devil had kept him from the Bible and true conversion, and now he was determined to be Satan’s sworn enemy. His preaching quickly drew the ire of Catholic officials. Emperor Charles V even issued an edict against Simons, offering a significant reward to anyone who might deliver him into the hands of authorities.

Nevertheless, Simons exhorted his fellow Anabaptist Reformers to reject violent means for accomplishing reform, advocating pacifism and separation from worldly power. His preaching and reforms were so successful that, eventually, north German and Dutch Anabaptists would be known as Mennonites. On the twenty-fifth anniversary of his renunciation of Catholicism, Simons’s health rapidly declined, and he died the following day, January 31, 1561, at the age of 66.

Misled No Longer

As the devil misled young Menno, so our enemy would mislead us, too. He would keep us from Scripture, from fearing God, from confession of sin, and from humble faith. May we, instead, “with sighs and tears” plead for and joyfully receive the gift of grace in our promised Savior, Jesus Christ.

Although I resisted in former times Thy precious Word and Thy holy will with all my powers . . . nevertheless, Thy fatherly grace did not forsake me, a miserable sinner, but in love, received me, . . . and taught me by the Holy Spirit until of my own choice I declared war upon the world, the flesh, and the devil . . . and willingly submitted to the heavy cross of my Lord Jesus Christ that I might inherit the promised kingdom. (Simons, Meditation on the Twenty-Fifth Psalm)

Recent Comments